make

explorations in a life generating design process

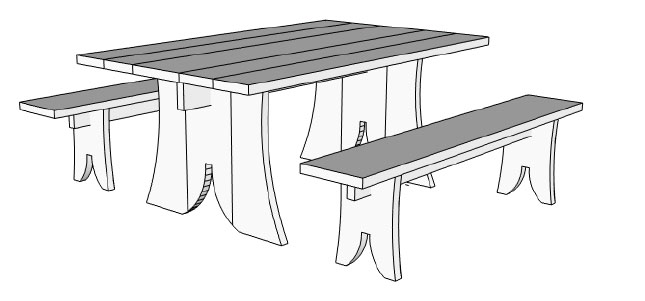

As a part of the Nature of Order seminar from the Building Beauty Program I was required to document a design process. On the this page you will find the unfolding design process of an outdoor table and bench. As well as that I have included how i made decisions through thinking, feeling, sensing and intuiting. In this post I have outlined the steps in which they were generated, as well as overlaid key reflections and insights from my learning journey within the Nature of Order module.

1. What to Design? finding a need that will improve our lives

There was a clear need for an outdoor table and bench to support our culture of dining together. We often take the kitchen table outside to eat on, however, due to it being a long rectangle it feels awkward sitting around it.

2. Finding a space for the table Seeking latent centers

Feeling the site for a latent center that would support and allow for the latent function of culture to emerge. A ‘latent’ center is a center that has the promise of life and has the potential to become a living center through design intervention. Creating interventions in latent centers is a way to leverage and then reinforce the existing strong centers in a place.

“The proper unfolding of wholeness is both an unfolding of space form the culture which exists, and an unfolding of a new (future) culture from the culture of the present (Christopher Alexander, Process of Creating Life, pg.348)”

3. Prototyping the dining experience with kitchen table and chairs Getting feedback from other users

Reflections

The strange proportions of the table and chair left me feeling disjointed to those around me.

– there was a significant discomfort in the layout

– the table as a center made up of centers that emerge to allow it to function as a ‘table’ were missing

– weird dimensions and layout meant when we were sitting we were not equidistant from each other which lead to a sense of separation from certain people at the table

– there was no center for the food to be left on the table

– it was hard to reach across the table from the ends

– the table without its inhabitants in the space felt like it didnt belong due to its strange dimensions and decoration

– the feeling of slight ‘unease’ caused by this lack of feeling whole does not support the culture of relaxed and comfortable daily outdoor dining

The Body as an Instrument

- Acknowledging the entire being as a center, a whole within a larger whole, with the ability to play a role in the unfolding beauty around us

- Our ability to be aware of the whole within us and around us depends on what faculties of perception we utilise

- Modern society and capitalism rewards thinking faculties over others and in doing so through our conditioning we experience the world in a certain way

- In seeking a more holistic perception and relation to the world, we are able to recognize the unfolding whole and work with unfolding living processes to create more life and beauty around us

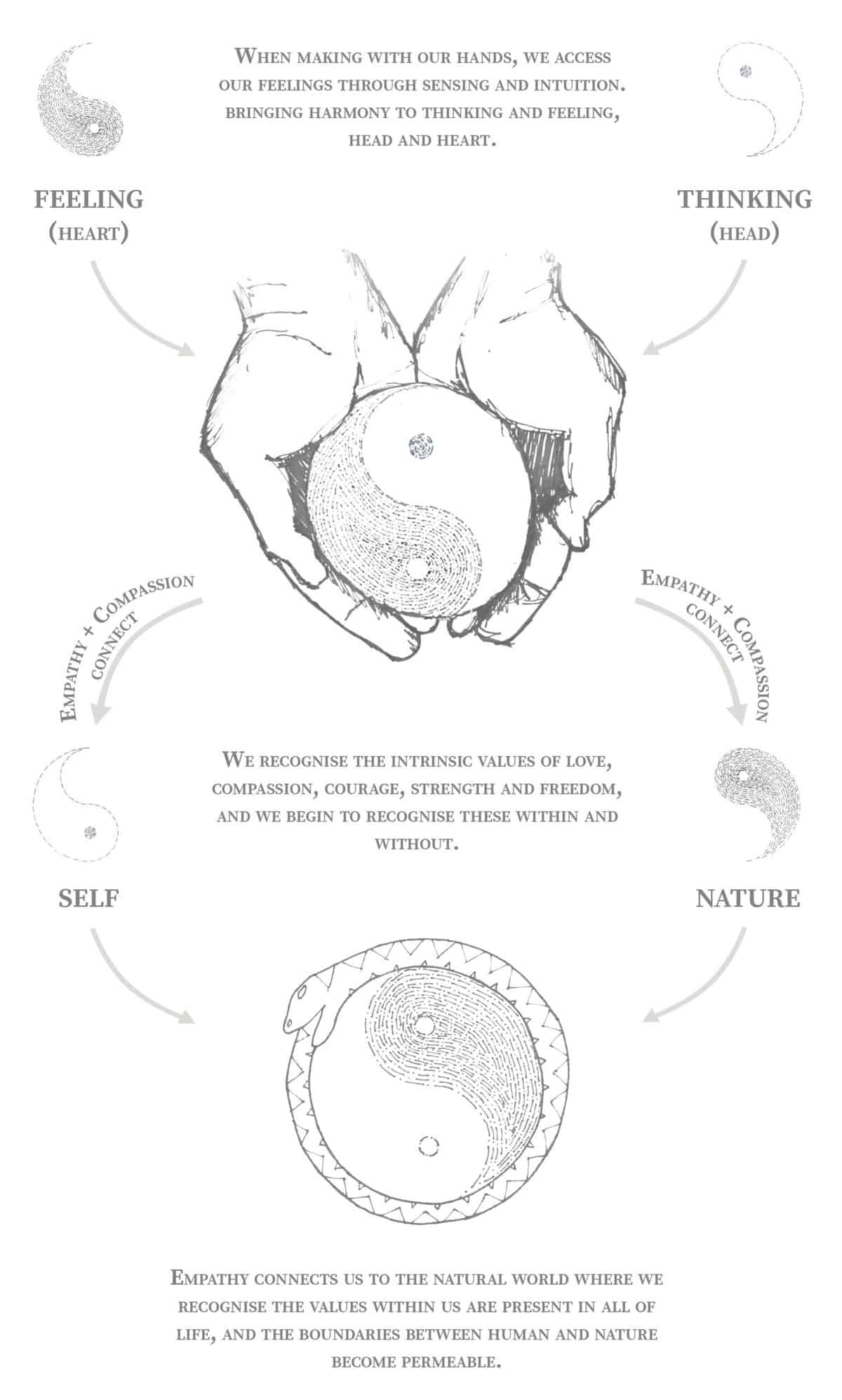

Jungs’ Mandala – The four ways of knowing

4. Observing further centers and patterns on site observing life in the field of centers

1. Sun, wind and shelter

2. Aspect – to the horizon from the table

3. Prospect – how the table would increase the feeling of life in the views towards the horizon and towards the forest and path

4. Existing bench filling the latent center of a place to enjoy the view

5. Other existing and potential uses and pathways through the site

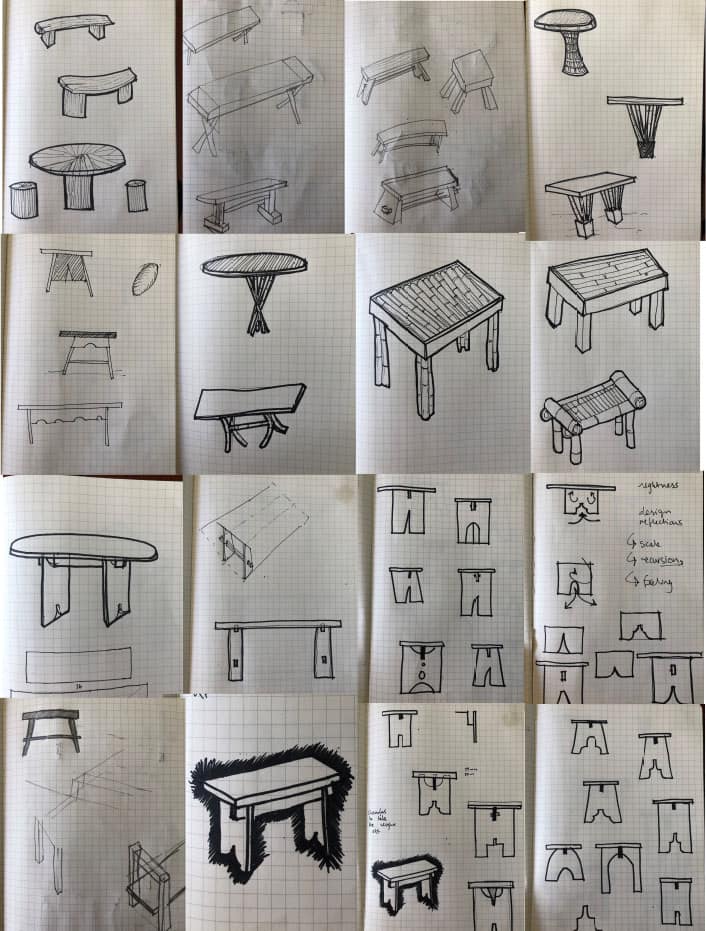

5.Sketching Ideas based on key principles outlined before

1. sketching design that use materials that are readily available – locally sourced eucalyptus and bamboo

2. Exploring ideas quite broadly but starting to pay attention to how it can be simply built taking into account the available resources of time and skill

3. Designing finer details – and seeing how they inform the feeling of the whole

4. Diving into the ideas of recursion and keeping a sense of feeling the whole is within the parts

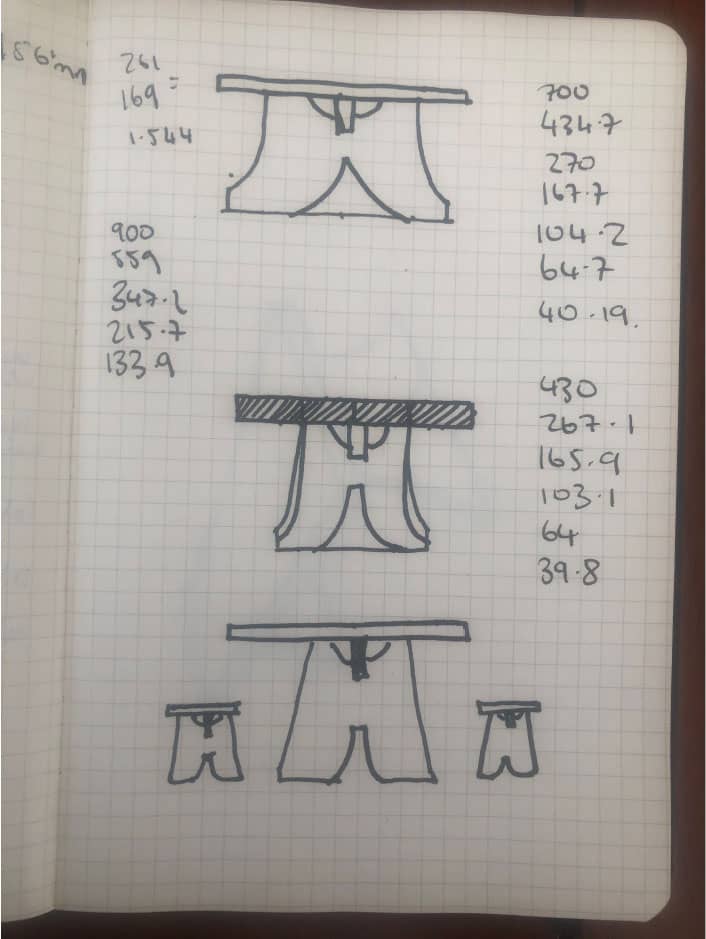

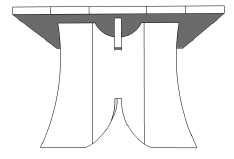

6. Designing the bench to be a recursive part of the table so that the feeling of the whole is within all the parts

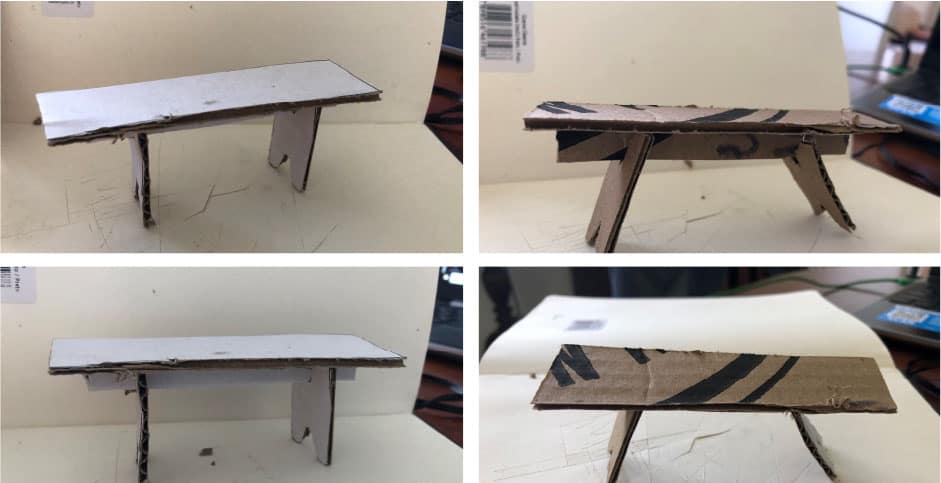

7. Making a quick model To get a sense of its feeling

8. Measuring tables and chairs to get a feeling for comfortable ergonomics and reflecting on their feeling

9. Making a small bench to test simple construction method Getting feedback through the hands from the materials and techniques

I started to make a small meditation stool to test the construction methods which I kept as simple as possible. The legs would connect to each other through a half-lapped stabilizing bar which then would fit into a housed joint.

Due to the nature of these joints, it became obvious that the timber would need to be dried, as the green eucalyptus cracked and twisted very quickly.

maintenance and renewal

“The simple fact of the matter is that once you build something, it deteriorates. We start this idea with the awareness of time, as the major deciding factor in how the object is going to age.”

Generally speaking nowadays from the time something is built it only begins to look worse. How can we design things so that their graceful aging works to enhance the living structure that they are a part of?

How can we utilise time as center through intuiting and sensing the emerging future and how can this enhance the field of centers and the sense of place?

In using locally sourced eucalyptus, it is hoped that the table would naturally silver and patina through time, an object that becomes deeply embedded in place and local culture.

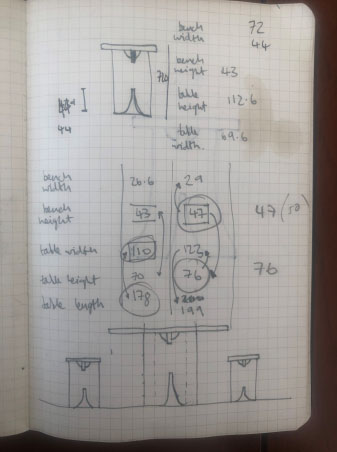

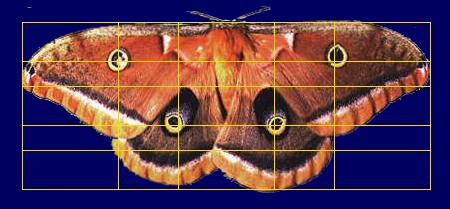

10. Using Phi to find harmonious relationships between the height, width and depth of the table

After measuring all the tables and chairs in the house and finding a range of good feeling, comfortable ergonomics, I then applied phi to these heights to find harmonious ratios between the tables and chairs.

11. Mocking up table and bench sizes testing 1:1 on site

- using the body as a measuring instrument to cultivate a deep feeling towards the experience of a sense of aliveness in real time – and iteratively making adjustments to the field of centers whilst discerning what brings more life to the whole.

- moving beyond idiosyncratic, little self preferences and moving towards the experience of the whole as the whole – through being a center myself within the larger whole.

12. Settling on a size that has a good feeling through observation and interaction

- walking around the table to develop a sense of its feeling within the space.

- sitting to get a good feeling of the size and connection to other centers.

- mocking up with plates.

- insight: when it was comfortable for 8 it was uncomfortably large when there were less people. Therefore we realised that we want it to be comfortable for 6 80% of the time and 8 for 20% of the time. When the table was big to fit eight comfortably, it felt too big when there were less people using it which had a disharmonious effect and weakened the table as a center.

“The living process can therefore be steered, kept on course towards the authentic whole, when the builder consistently uses the emerging feeling of the whole as the origin of his insight, as the guiding light at the end of the tunnel by which he steers (Christopher Alexander, Process of Creating Life, pg.371)”

13. observing the larger field of centers seeing how the mockup interacts with the larger whole

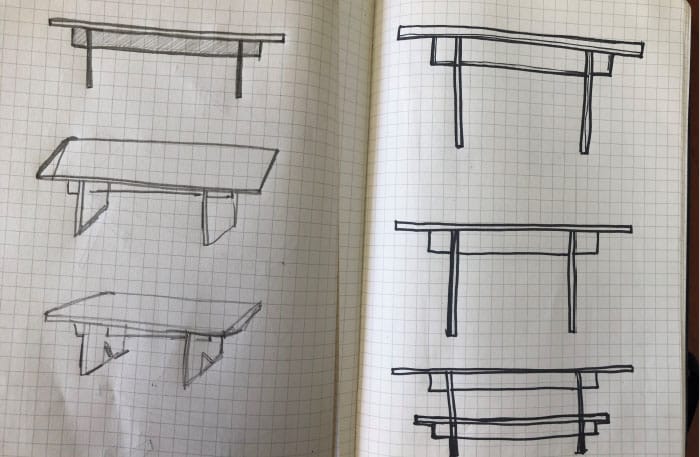

14. mocking up table legs using cardboard in search of good shape

- Through working iteratively adding and subtracting cardboard based on intuitive and felt decisions interacting with the direct feedback loop of feeling, it was possible to quickly work towards a shape that was enlivening within the larger field of centers.

- Using simplicity – what is the simplest next step in the process that can increase life in the existing centers?

- I noticed that each step in the process unfolded with symmetry.

15. applying phi to the design of the legs refining previous with 1:1 paper mockups

- I applied the ratio of phi to key dimensions based on the best version of the previous step in the process.

- In making simple modifications in each step of this process I was able to do A/B testing for which designs were more coherent in relation to the rest of the design.

16. Using digital modelling to calculate cutting lists with caution to not design with sketchup

Generated vs Fabricated structure

in a fabricated process and the resulting structure, we project ideas and concepts outward from our minds into objects in reality. oftentimes these projections come from our conditioned ideas and include an attachment toward them from our ego. In a deeply felt generative structure we design from a place beyond ego, a place that is connected to the universal Self. In designing from a state of presence that utilises our feeling, sensing and intuitive faculties, we are able to design from a place that is beyond our idiosyncratic likes and dislikes and create beauty as an extension to the larger beauty to which we all belong. In a generative process, we embody presence in each design step and naturally allow beauty to unfold.

17. Recursive design of bench legs applying unfolding sequence of table legs to the benches

In applying the exact unfolding pattern sequence of the table chairs to the bench chairs, I found it didnt look good and that some modification would be required to get a good feeling. In using paper to mock up the bench legs I was quickly able to prototype a beautiful leg that I was happy with. In doing this the benches and tables as centers strengthened the whole through their connection the emergence of alternating repetition between the benches and table.

18. Creating final cutting lists in sketchup

I digitally modelled the hand drawn bench legs and added them to the model with the table to be able to compile an accurate cutting list.

Despite being a representation of the final design, it is by no means an accurate one of how it would feel. In an ideal situation, I would mock it up exactly as above to see how it feels and to make adjustments based on that. That being said I feel confident enough about the feeling of the table and bench based on the prototyping that I had done to make a start. Now to just get on with it…

closing thoughts

“Our ability as artists depends very largely on our ability to experience, formulate, and carry such a feeling — first to feel it and witness it, then to carry it forward, remember it, keep it alive within us, and insist on it (Christopher Alexander, The Process of Creating Life p.382).”

At every step within this generative process, I couldn’t have anticipated the outcome. This was interesting on a personal emotional level and I noticed that as long as I was able to be fully present with the process, I was able to be within the process of unfolding life. In moments of lapsed presence, the default mode becomes one of projecting conditioned unconscious ideas, thoughts, and ways of relating to life, which is sadly rooted in separation from all of life and not connection. In the present moment, we are connected to the flow of life and it is only from this place that we can sense the emerging future through finding and entering the grain of the unfolding world and following its course to a living future. Modern life and ways of experiencing the world follow a course outside of this grain and the opposing resistance continues to create further separation between human-nature.

Working to create life in generative design processes is similar with natural living processes in the sense that they are often in direct conflict with the values of modern life and economic world views. The world experiences this daily with increased pollution, loss of diversity, and daily species extinction, all as a consequence of human thinking and systems whilst all the while economic markets reach their all-time highs. Going forward I am excited to explore the resolutions between generative processes and the modern economic system so that the positive benefits from this work can be appreciated and scaled for the benefit and enjoyment of all of life.

In using the faculties of deep feeling, sensing, and intuiting within the design process, I found that I was able to connect deeper to the present moment and to the phenomena in my experience. This direct engagement with full-scale mockups within the manifest world enabled these other ways of knowing the world to become activated, and for thinking to fall backward and become secondary. Engaging with the present moment in these ways brought deep peace and joy, which feels as though it was due to being connected with a life-generating process. It is almost as if beauty emerges through attention and presence which is greatly aided by making. I look forward to exploring these feelings further in future projects.

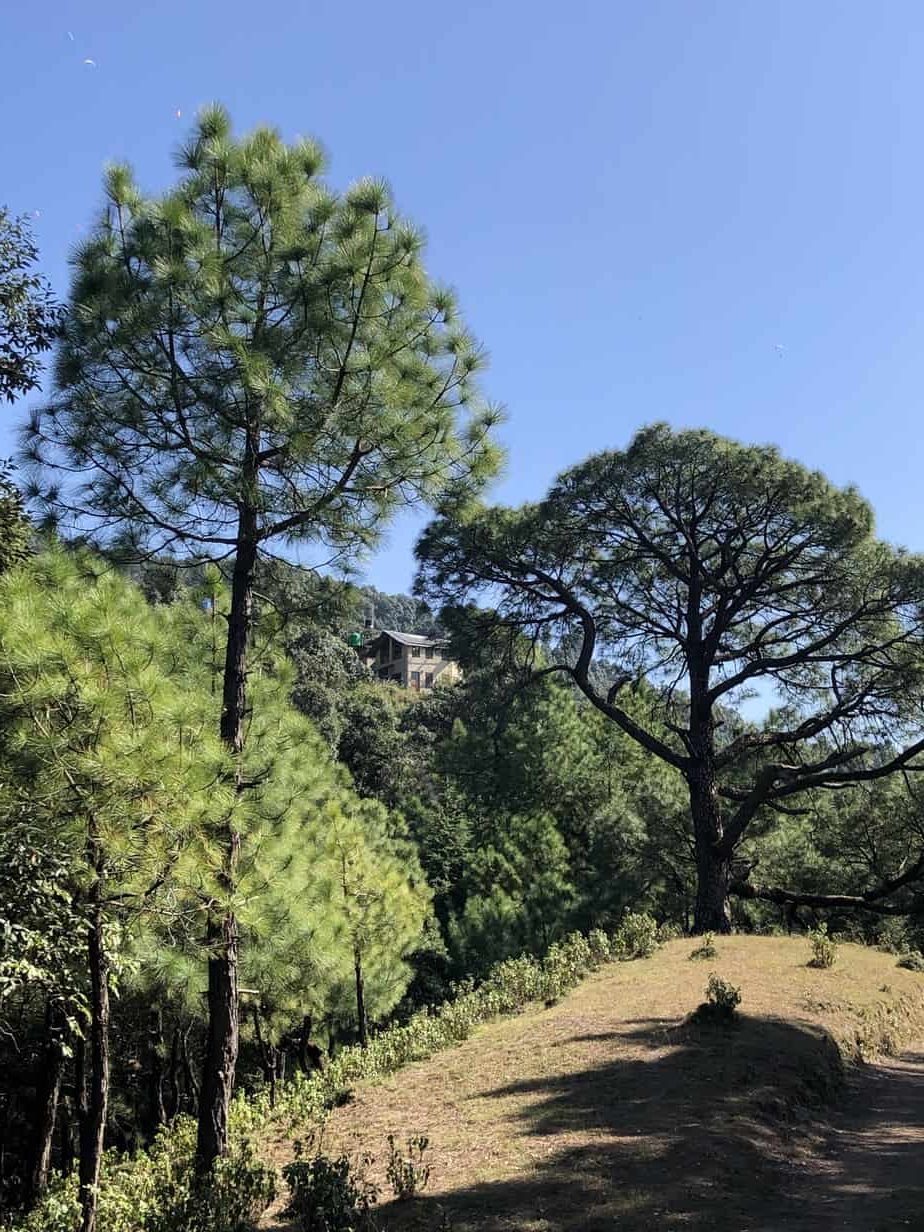

dharmalaya autumn 2019

In October I returned to the Himalayas to spend a month at Dharmalaya; to reconnect with the place and people and to digest some of my experiences from the previous year at Schumacher College. I had a very renewing and uplifting time being on the land and with my extended Indian family.

I participated in a yoga retreat called the yoga of nature which was filled with many opportunities for introspection and reflection. It was a nourishing space to be in and gave me some clarity about the qualities of being that I want to cultivate and bring into my life and work.

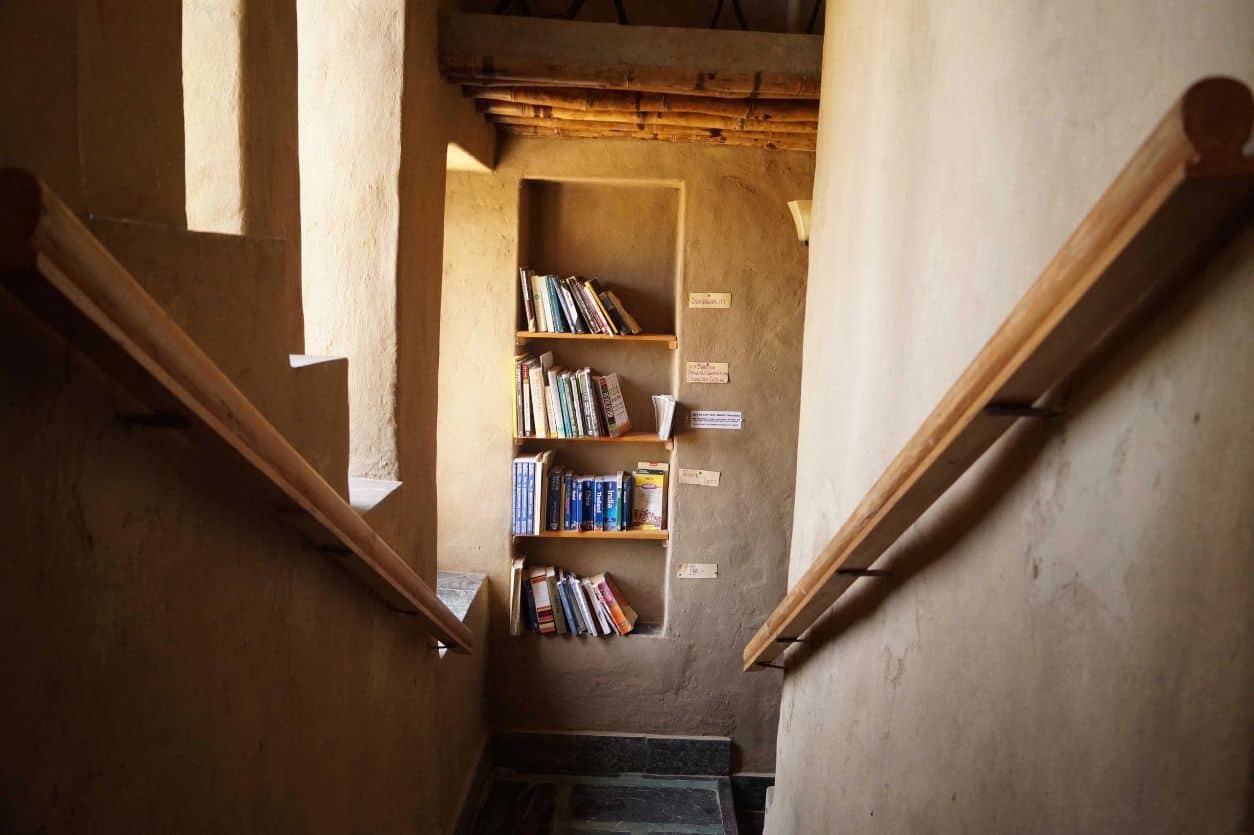

It was beautiful to see how the buildings that I had been a part of had gone on to evolve and unfold in that very slow and beautiful way that things do here. It was great to see the finer finishes in the duplex and meditation cottage and that they were looking better than envisioned. The bridge and upper section of the dormitory look and feel great. The upstairs space is well lit and has a good balance between opening out to the world and being a cosy space to retreat into.

We got started on the outdoor seating area with a new group of volunteers and interns. It was good to see life being brought into this space as it had been empty but full of potential as two and a half years prior we constructed a 10,000-litre ferrocement water tank here.

Here are some pictures from my time in paradise in the hills.

thinking with my hands, feeling with my heart

Whilst studying Ecological Design Thinking at Schumacher College I undertook a research project titled, ‘Thinking with my Hands, Feeling with my Heart’. I explored how craft can be a catalyst for healing the separation within individuals between the human and natural world. I make the argument that the designer should seek, as a practice, to bring unity to the conditioned lens of separated perception through connecting with the natural world whilst making. I highlight the importance of the designer becoming aware and refining his/her perception of connection with nature as a means of proper meta-design. So many design solutions to social, cultural and ecological challenges at first seemingly solve the problem, though go onto creating second, third, fourth-order problems. This is due to the deep interconnectedness and complexity of our human systems with each other and the natural world. Through the same separated lens of perception or level of thinking, we will continue to make solutions and further problems based on that degree of thinking. The challenges we face require a radically different way of thinking to create well-refined solutions with their essence being connected to the whole.

I outline a process of getting out of our heads and connecting inward to our hearts through the sensorial realm of making, inspired by the work of psychologist Carl Jung. This work is by no means complete or polished and outlines my journey, and process of practices that I followed. It is not to say that I too have healed the separation myself, but having had glimmers into perceiving differently, I recognise the importance of it and understand the work that is required to shift my perceptions. This journey will be for the rest of my life.

This work developed my understanding of the importance of working to better understand the inner dimensions of my life so that the work that emerges is from a place of clearer clarity. I see the potential that conscious making has as a catalyst that aids the work of the designer/maker to create a more beautiful and harmonious world and to design solutions with the whole in mind.

To read the full paper click here. I’d appreciate any constructive feedback, comments and suggestion 🙂

canoe

I built this canoe with my friends Will, Liam and Joe over a long weekend in the Lake District.

She is made with poplar ply, spruce for the gunwales and locally sourced oak for the seats and handles. At 15ft she only weighs 25kg making her easy to handle by one person. She is as graceful in the water as she is on the eyes and great fun to paddle.

As a part of my dissertation titled ‘thinking with my hands, feeling with my heart”, I conducted some research on how individual heart coherence can influence the coherence of a group whilst making. More information on these insights can be found here.

dorodango

Dorodango’s seem to be a craze (borderline obsession) that earthen builders seem to find themselves drawn to which seems natural when you realise the beauty of applying presence and patience with earth to create unbelievably shiny and precious beautiful yet deeply meaningful and seemingly pointless objects. The Japanese art form, Hikaru Dorango is literally translated as shiny mud dumplings which is precisely what they are. The origins of the craft trace back to a school playground in Kyoto where children were found to have started making them.

I was drawn to Dorodangos as a tool to study conscious making as part of my research titled thinking with my hands, feeling with my heart. During my first encounter with the craft, I realised the immediate feedback from my inner state of being with the lack of lustre in the balls. Once I’d realised this, I took a walk and released the grasping of ego and mind, and then returned to work on the ball with a renewed sense of presence. Not only did a beautiful shine emerge, but it came with ease and joy. This started my experiments in working with Doradangos in my research and lead me onto studying the effects that making has on the coherence of heart and mind. This part of my indicative research was done using the biofeedback device developed by the Heart Math Institute which I used to facilitate a conscious making experience with a group of 15. A page from my research is below.

I believe making Dorodangos to be a transformative experience for anyone, any age. Below are some of the reasons why I believe so…

- To connect to yourself inward, whilst connecting outward into the world

- To be in the process, and to allow a flow state to emerge through mindfulness in the process

- To find joy in the unfolding of beauty

- To find perfection in imperfection

- To work with the head, heart and hands

- To be engaged with a living process

- To be process-oriented opposed to goal-oriented

- To be in contact with the web of life and to live in the moment with a direct connection to the web of life

If you are interested in me hosting a workshop with your forest school, business, university, knitting club etc. I’d be more than happy to. contact me here

place and nature as pedagogy

In this project whilst at Schumacher College, we were drawn to explore our direct and embodied experiences of our human-nature embodied in the present moment and connected to place as a means to heal the separation with nature that the modern world conditions us with.

We explored the idea that in connecting to the spirit of place by becoming aware of the qualities of aliveness in a space, we are able to connect deeper to our own true nature, a nature that is whole within and with all of life.

As the mind settles we become perceptive to the wonder-filled lessons that nature has to offer, without any of the preconceived ideas or judgements of the mind. Nature is the eternal teacher.

The platform is placed in a way that feels tall within the trees to naturally aid in sharpening the senses and the attention of the sitter. Whilst canter-levering above the stream, a feeling of expansion into place occurs as senses merge out into the surrounding landscape. We placed the platform in a way to reduce the friction in the mind and the sitter to connect to the landscape. Through the use of a balance stool that requires constant movement and presence to stay centred, we created a further experience to aid in the embodiment of the mind in place.

This project was inspired through spending time contemplating within the forest, climbing trees and connecting to the spirit of place.

The structure of the prototype was designed to be constructed, moved and adapted easily using clamp mechanisms around the trunk instead of direct fixings into the tree.

dharmalaya process

The majority of my time at Dharmalaya was spent working mainly on two buildings – the duplex and meditation cottage. They are both constructed in a similar adaptation of the Kangra vernacular style. They have stone plinths, load-bearing adobe walls and timber, bamboo and slate roofs. Both buildings are sited on existing terraces, and each building has its quirks where new design elements were tested.

I found the workdays deeply satisfying and enjoyable. We would start the day with a circle where we would first check-in with one another which was then followed by discussing the workday ahead with local staff and volunteers. I enjoyed the rhythms of the day, rising early for yoga and meditation and restful evenings after an early dinner during sunset. Thanks to the hard graft my body clock synched with the natural cycles of day and night as well as the seasons, where I slept more in the cold of winter.

During my time here I learned to build the way the local artisans build, directly from them, just as they did from their masters. In learning these ways, often through observation and correcting alone due to the language barrier, I felt an embodied connection to the lineage of craftsmen in this region and to their timeless way of building. In doing so, I developed a deep appreciation for the vernacular methods and buildings that had emerged over countless generations with this land and it was a privilege to be an outsider given the chance to experience these subtle and deep beauties.

Working alongside the local villagers, I was able to experience the way they work and live, and the lack of defined separation between the two. What was noticeable was the sheer presence, awareness and connection they exhibited in every moment with every action, something that was alien to me and my way of life. Whilst working at Dharmalaya I was inspired to cultivate working in these mindful ways, taking my work slower, but savouring and enjoying all of the life that was flowing through it. These practices were slowly learned, as the tendency of my conditioned mind was to become distracted easily through judgement, criticism and all manner of noise that the monkeys in my mind would make. This exploration into conscious work and life is one I’ll walk for the rest of my life.

Here is a selection of photos from my time growing buildings in the hills.

dharmalaya arriving + impressions

As the earth began to warm from the first of the sharp spring sun falling in the foothills of the Himalayas, I travelled to the village of Dhanaari, a 40-minute walk from the nearest town of Bir, 2000m above sea level. As I hiked with my bags up towards the mudhouses on the hillside, I was filled with excitement and angst of what was to come. I paused on a fallen log to catch my breath and begin to settle into the land that would become my home for the next year. As I sat here, ignorant of what experiences lay ahead, I dreamed into who I wanted to be and become.

I had arrived at Dharmalaya, an intentional educational community devoted to compassionate living. I was here as one of the first international architecture interns and I had come to learn to live a life that was in harmony with nature; my inner nature and all that lies beyond. Living in a community I shared my life with many beautiful people from India and further afield. I found learning and working in the community was simultaneously nourishing, challenging and hugely rewarding. Life at Dharmalaya was centred around the wisdom traditions of the region and in day-to-day life, we put into practise the Indian ethical principles of karuna (compassion), ahimsa (non-harming), metta (loving-kindness) and seva (service). And in this manner, I learned and practised living responsibly and sustainably whilst cultivating awareness and reverence for the sacredness of all of life.

Leading a life that was deeply embedded in place and community taught me a different way to live and be in this world. Living (including working) consciously in a more present way, enabled me to connect deeper to the natural cycles, rhythms and patterns of life around and within me, and in doing so life became more vibrant and fulfilling. I began to take myself and the world less seriously which paradoxically made more space for me to care for the things that I feel mattered the most.

The first few months here were filled with new experiences daily as I participated in workshops centred around compassionate and sustainable living, earthen construction and silent meditation. This time was filled with fast and slow learning on many fronts exploring our most innate but largely forgotten human values. Through living the values of kindness, service to others and compassion daily, I soon grasped how these were to be applied in the way we design and build.

I worked on two major building projects during this period, a two-story duplex and a meditation cottage. These buildings were made using the vernacular methods of the region using stone, adobe, timber and bamboo but were designed with the comforts of the modern person in mind. The majority of materials come from the land itself but the addition of a few market materials ensure that the buildings are earthquake-proof. This way of building was revived by renowned Indian architect and one of Dharmalayas influential faculty, Didi Contractor. These techniques have sadly been replaced in the region due to the perceived social ideas that having a concrete house is more advanced and developed than having a mud house, and sadly people in the village are trading their healthy earthen homes for concrete homes. This short thinking is sadly causing harm to the inhabitants as harmful mould thrives on concrete in this climate. Dharmalaya works in keeping this information and wisdom that’s been rooted and evolved with the place and people for thousands of years alive. Building in such a low-impact manner can be seen as doing so in the most compassionate way for the land and people. I see the potential in these methods and philosophies as being a powerful catalyst towards cultural, economic, social and ecologically regenerative practices in this bioregion.

Inhabiting a space that embodied the values of compassion, equality and kindness was the perfect teacher in reflecting the qualities that I wanted to cultivate. I am hugely grateful to all who were involved in making my time here so nourishing and beautiful, you are all family.